Generative or Permutational Art? The Case of Abraham A. Moles

Along with a few thoughts on degrowth and AI

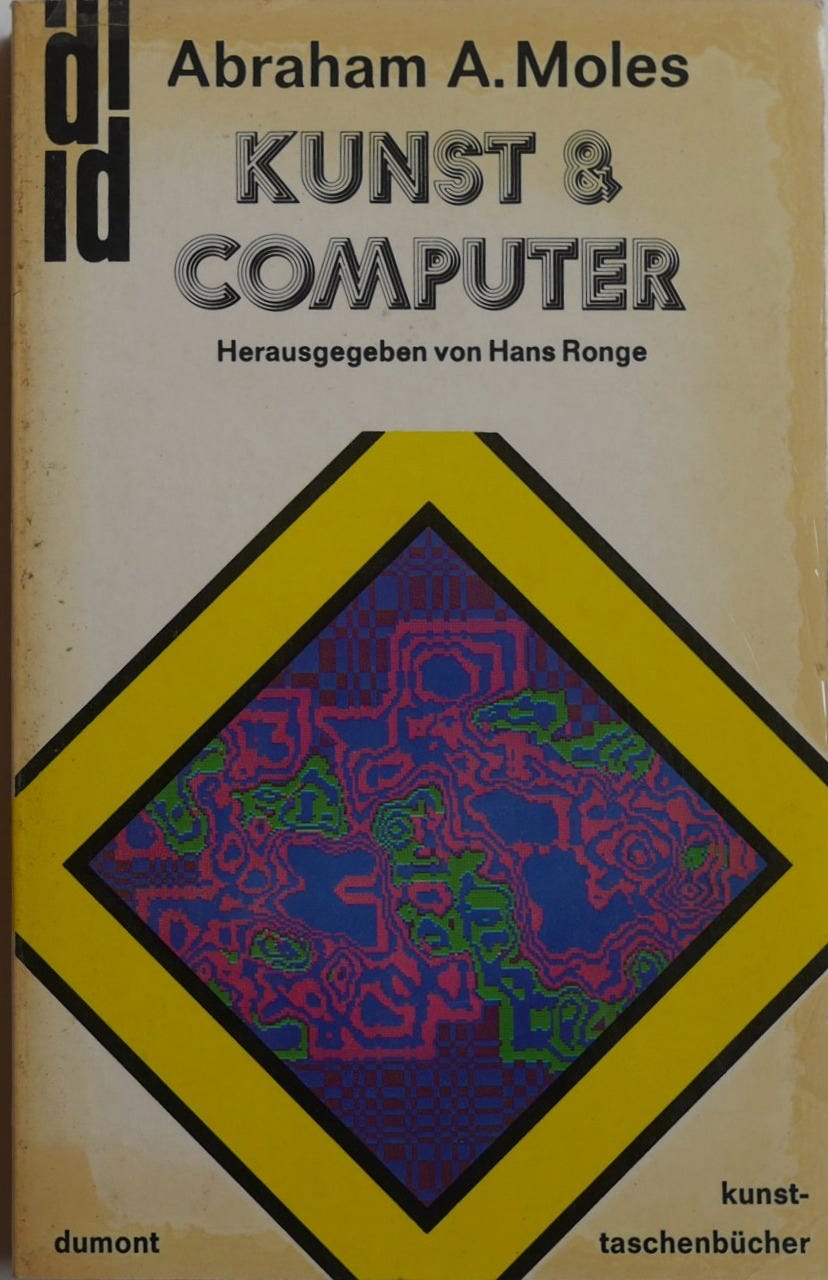

This past week I’ve been working on a proposal for an English-language translation of Art et Ordinateur (1971), a book by the “information aesthetician” Abraham A. Moles who wrote on permutational art, but with very few books and articles translated to English. Along the way, I’ve been finding myself asking questions about the relationship between permutational and generative art, both past and present.

I became familiar with Moles during the first semester of my PhD program when I wrote a paper on the New Tendencies, the Zagreb-based platform for an international set of artists making work according to the logic of structures, instructions, and “programs” as a form of visual research. Since the establishment of the first New Tendencies exhibition in 1961, the artists associated with the platform have been lumped into an array of categories ranging from kinetic art to concrete art—and more divisively, as Op art. Their works often looked quite geometric, with visual and perceptual resemblance to the field effects of gestalt psychology such as those shown by the psychologist James Gibson. Jack Burnham saw the work of the New Tendencies as linked to expressions of quantum physics. This was an era of permutational art, a term which doesn’t get as much play in histories of present-day work with AI and algorithms as generative art.

But looking back to Moles’s writings and discussions of permutational—rather than generative—art has much to do with considering the limitations of AI in visual practice today, as well as the types of roles humans can play in them. With generative art, we often think of conceptual and computer-generated art related to algorithms that set up autonomous (or mostly autonomous processes); Sol LeWitt’s “the idea becomes the machine that makes the art” is often invoked here as a link between the computational and other formats. Chance-based processes and infinite series are commonly cited characteristics as well. Permutational art, meanwhile, does not need to invoke an origin: previously set units can be rotated, arranged, and played with in the present.

There can be overlap between the two. As put by artist Nicholas Schöffer, the generation of new outputs may or may not be an aspect of generative art: “A permutational series has the advantage of generating a very long nonrepetitive cycle from a set of much shorter sequences.”

I haven’t yet figured out why generative art gets more mention than permutation. My feelings so far are that generation is about futurity, bigness, and moreness—these are useful terms, really— rather than permutation, or adjusting what’s already been given in the present. Limitless expansion comes into play more with ideas concerning the infinite recombinations of AI, more than its limited permutations.

I want to link up permutation to concepts of degrowth, which concerns issues of scale in the present linked to economic and social equity, in contrast to longtermist concepts of existential risk that prioritize the colonization of space and Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) over the lives well lived in the here and now. Choices about which type of world we want get expressed in the processes valued in art. Can we consider the limits of generative art as much, if not more, than its infinite expression?