Everything Looks Like AI

Is it confirmation bias or digital saturation?

On a recent trip to Chinatown galleries, I kept on seeing paintings that looked like they had been made with AI. I don’t mean that they were printouts from Midjourney or any other prompt-based image generator. Instead, it seemed like the paintings retained traces of the machine-learning process: a few extra fingers here or there, smudged outlines where a body had failed to render, and small variations enabled by slight changes to text-based prompts. In other words, digital logics had entered a formerly—and emphatically—non-digital space.

This type of “painting after AI” can be seen in repetitive, surreal combinations. Matt Kenny’s Tower Paintings show the World Trade Center as a type of techno-monster, though with slight differences each go around. This is the iterative logic of typing in a prompt “World Trade Center, cropped to show the top, but make the windows have eyeballs and it’s realistic.” Then, the next one: “Do the same, but in a close-up shot.”

The friend I saw the show with didn’t get what I was seeing. Don’t all painters work in serially, in process?

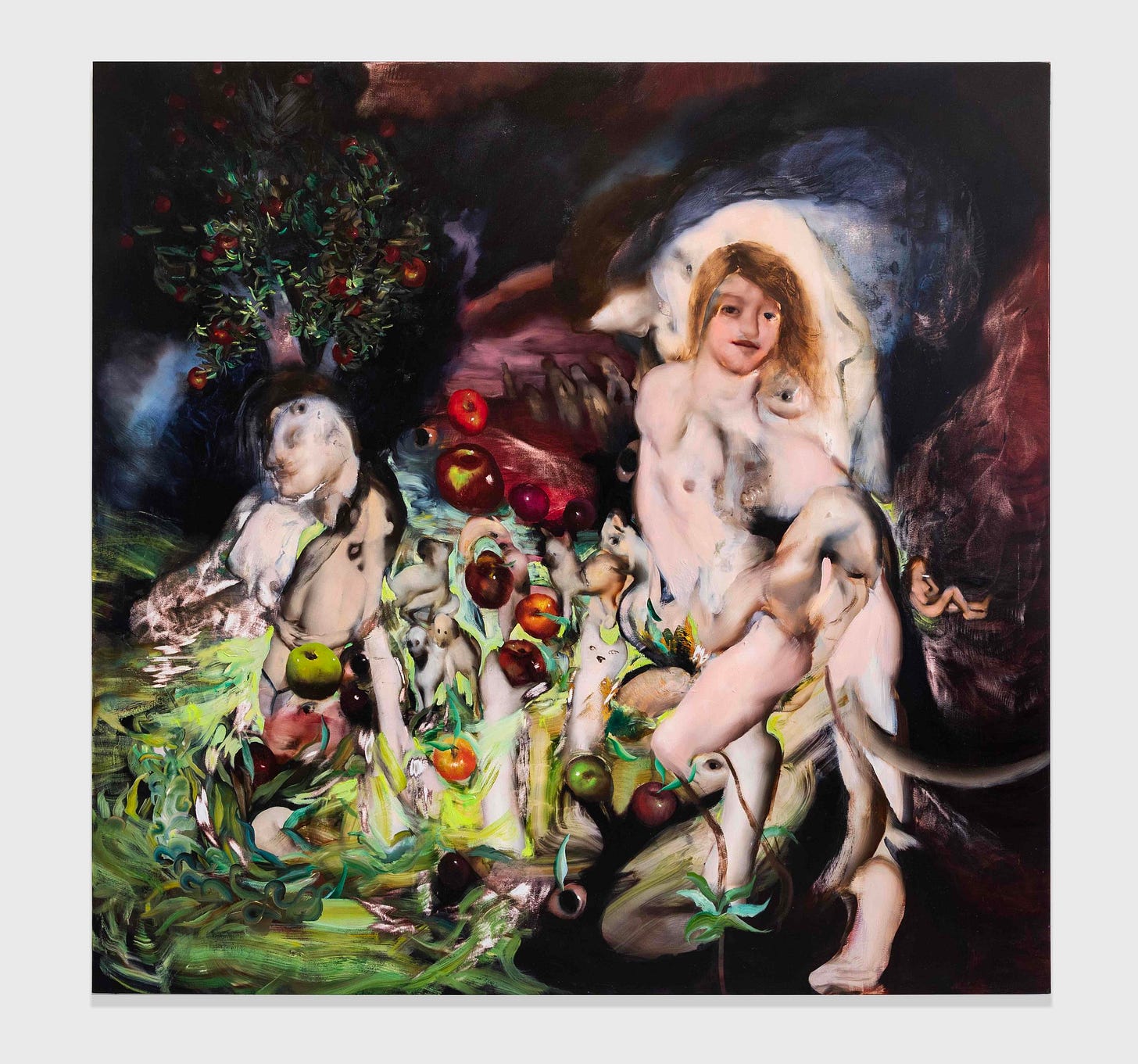

But what about the blurred interconnections of figure and ground that appear when a prompt gives too many terms to consider each in full detail? Faces are missing, plants are incomplete in the partial render, before fully committing to one type of prompt-based probability.

This is a painting style that fluctuates between possible states, already in wait for the next tweak to a prompt.

Ambera Wellmann is another painter who makes paintings in the style of an AI generator, though with more of an obvious touch given the telltale smudges and extraneous limbs in her mish-mash tableaux.

As someone who spends a lot of time online and thinking about AI, I know I could be suffering from confirmation bias to some degree. But I don’t think I’m wrong, which is why I’m looking forward to writing a longer essay on AI logic and non-AI painting.

What do those prompts return when you ask dall-e