The first two exhibitions I wrote about this week were okay, not great. It’s easier to write about historical context or point out flaws than it is to write about what’s good, especially without coming across as a fan with blinders on. In lieu of trying to write an actual review about a show I liked, I have a few statements to make: it’s a series of propositions, not nearly speculative or fierce enough to be a manifesto (although eventually maybe I’ll write and edit a more thorough version.) These statements or theses on techno-utopianism come in response to Stan VanDerBeek: Transmissions, which closed on May 4th.

Stan VanDerBeek: Transmissions

Where: Magenta Plains (149 Canal Street)

1) Just because an artist works with new forms of media and technology doesn’t mean that they’re utopian about it.

There’s too many different ways that artists involve technology in their work to make generalizations about a consistent utopian ethos. Trevor Paglen’s work reveals the black boxes of the military-industrial-tech complex. Artists making work on blockchains or who are minting NFTs might be utopian about the potential for new forms of community and autonomy, but some are seeking greater autonomy in their professional practice away from galleries. Dora Budor’s Lifelike (2024) at the Whitney Biennial attaches a vibrator to one of the symbols of 21st century tech, the iPhone, to provide a glitchier take on the influencer video. Among these three examples, an entire network of approaches to the social life of technology comes to view. Artists who seek to find different and new uses for technology and media away from their intended designs by the military-industrial-tech complex does not mean they’re utopians.

2) The term “utopian” or “techno-utopian” is a conversation stopper: it rules out further engagement with an artist’s work.

3) Among the pejorative utilizations of the term, “techno-utopian” often gets used when there’s not an obvious political engagement.

4) Stan VanDerBeek was not a techno-utopian.

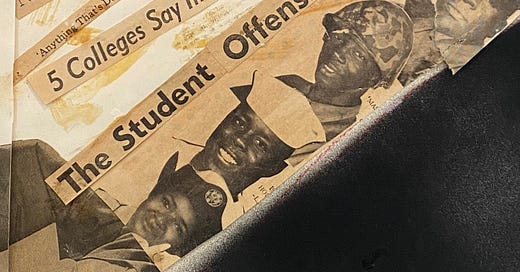

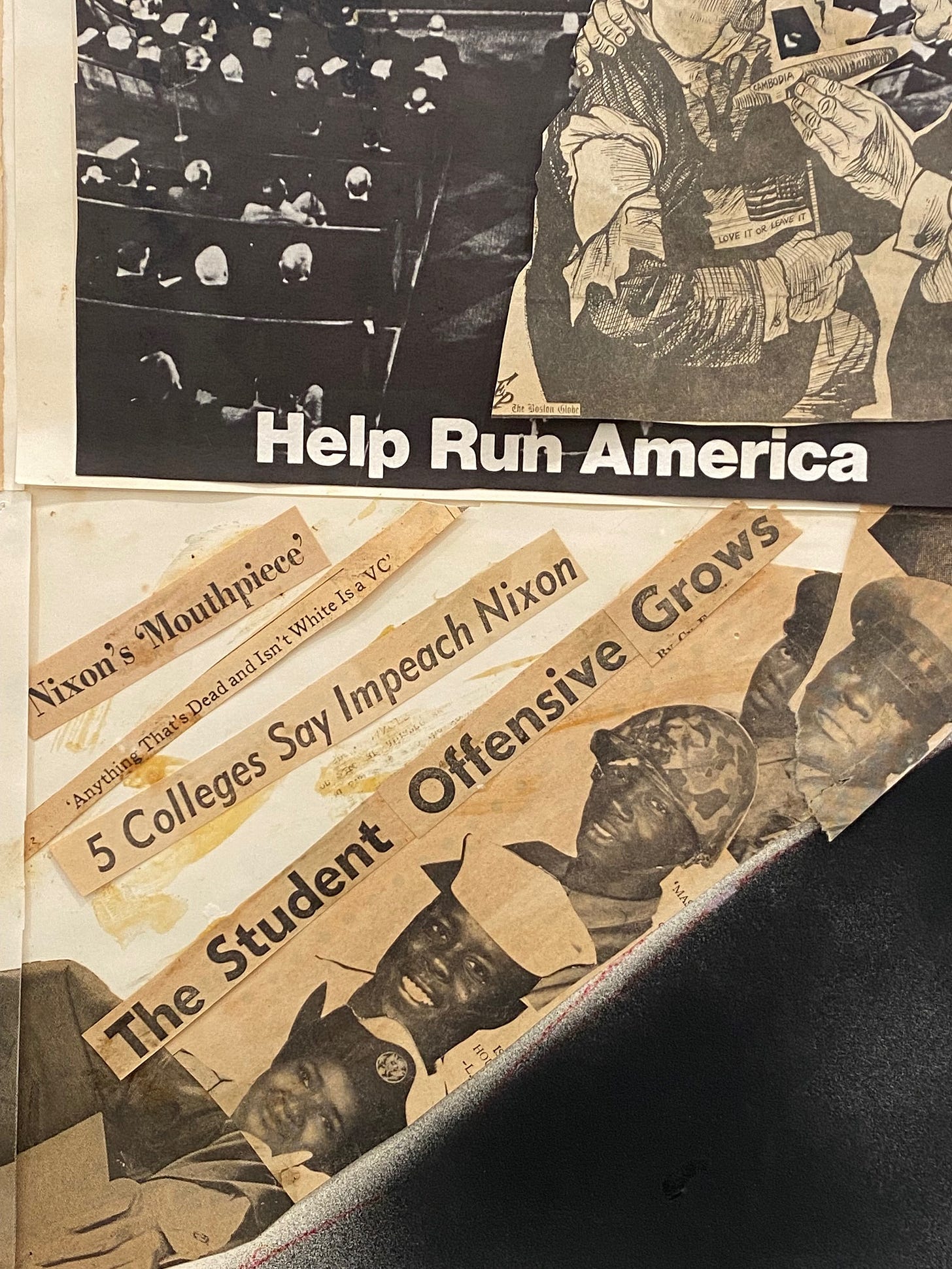

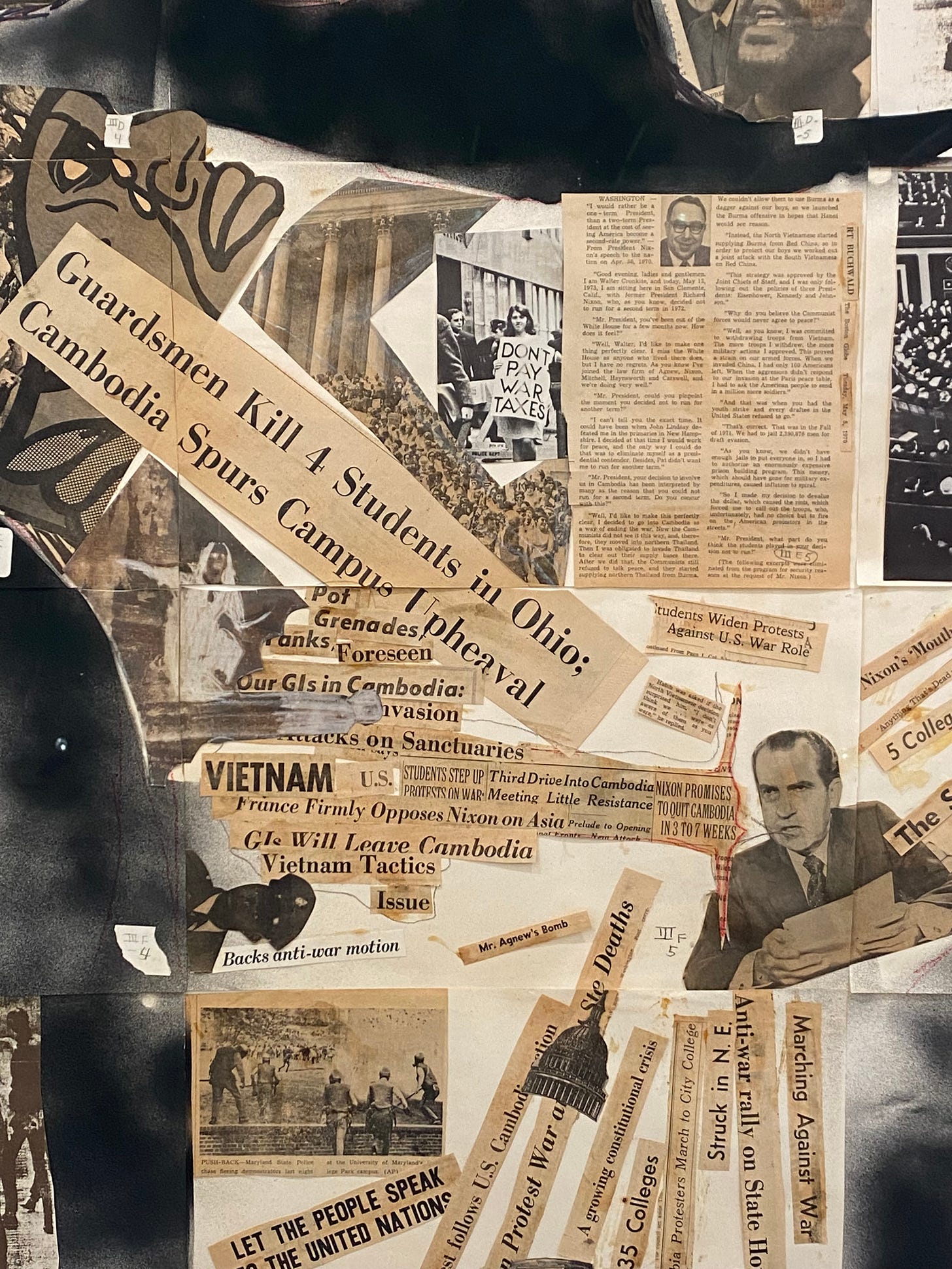

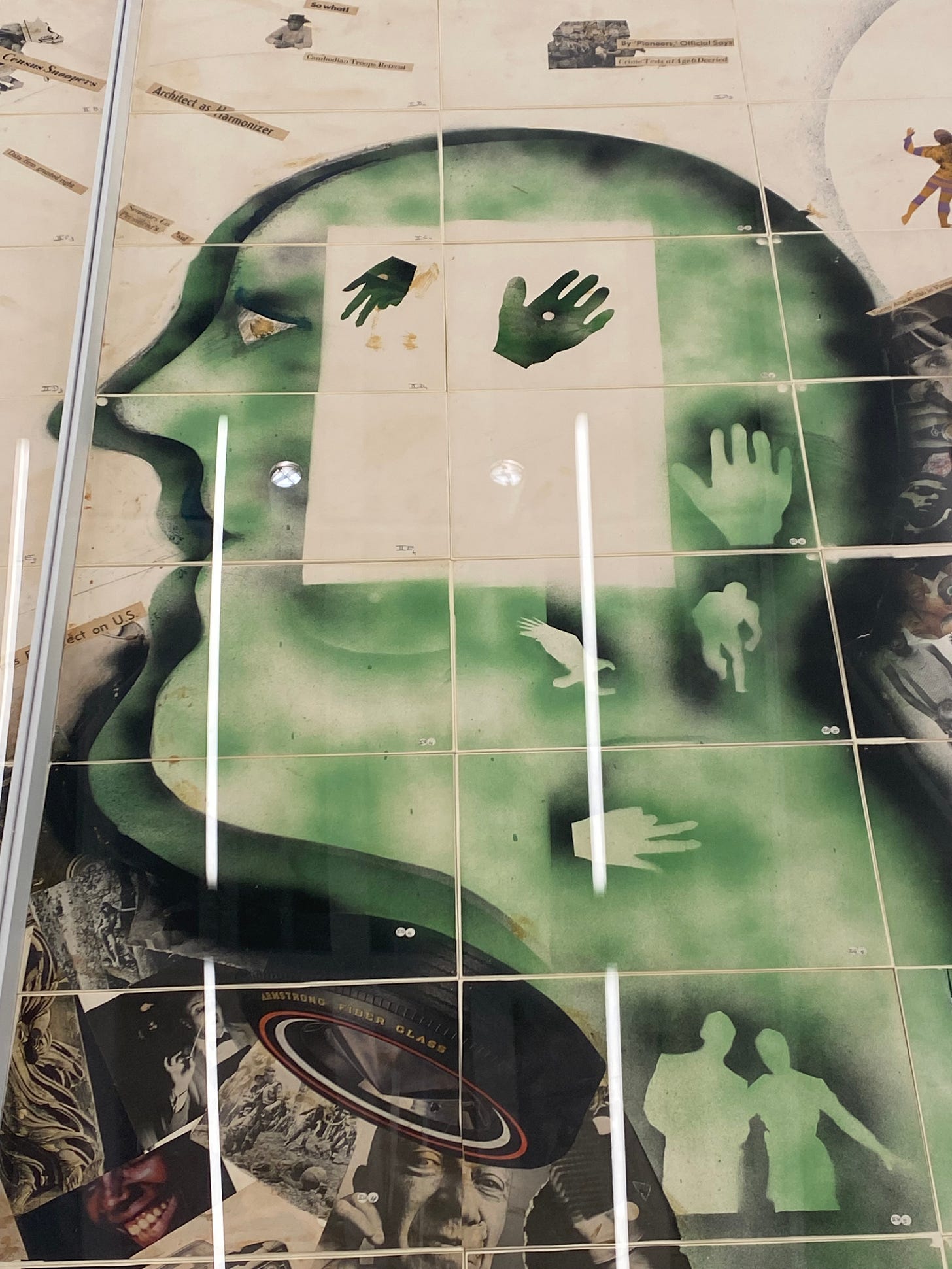

The main reason I visited Transmissions was to view the original and faxed copies of VanDerBeek’s Panels for the Walls of the World: Phase II, a mural sent by fax while in residence at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) while György Kepes was the director there. I’ve written about the mural before, but only in terms of how one version of it was proposed—then went unrealized—for the Software exhibition of 1970 at the Jewish Museum. While fax-based technology had existed prior to the 1970s, commercial development for its use in business was growing with Xerox; VanDerBeek used their telecopiers for Walls of the World. VanDerBeek’s residency at CAVS helped with the ability to utilize such tech. After all, as far as conceptual art and intermedia trivia goes, Seth Siegelaub’s Xerox Book exhibition of 1968 wasn’t made on a Xerox copier because nobody would give Siegelaub access to those newfangled office machines. Like today, there’s still a number of residencies where artists go to have access to resources, but that doesn’t make them technophilic “utopians” about tech.

5)To be a techno-utopian is to speculate upon advances at the societal level based on the rationales of technology.

As put succinctly by Howard P. Segal:

Technological utopianism derived from the belief in technology -- conceived as more than tools and machines alone -- as the means of achieving a 'perfect' society in the near future. Such a society, moreover, would not only be the culmination of the introduction of new tools and machines; it would also be modeled on those tools and machines in its institutions, values and culture.

Where is a “‘perfect’ society” to be found in this exhibition? VanDerBeek’s faxes show a distribution of art across time and place, which Stephen Frailey in the Brooklyn Rail writes about quite nicely in terms of giving collage an update. VanDerBeek’s works supply different, non-normative applications for tech, opening up to new ontologies and experiences with its materials. He’s not advocating for more of the same based on how these tools and machines are used by its current “institutions, values and culture.”

6) “Utopianism” refers to a generalized description of aims instead of stating what, specifically, the works are doing and what they’re advocating for, rather than some fuzzy, as-yet-untested utopia.

For instance, VanDerBeek advocated for disposability and impermanence in art and life. If we were to say he was utopian about anything, maybe it would be through the belief in materiality as a way to alter current art and society.

I do write a little about VanDerBeek in an upcoming, as-yet to be published paper on the artist Les Levine. In the 1960s, both VanDerBeek and Levine were interested in making art that was “disposable” in order to change antiquated traditions of the art world, in which one must make a permanent-seeming object to be sold by a gallery to museums or individual collectors. VanDerBeek’s essay “Movies, Disposable Art, Synthetic Media, and Artificial Intelligence” described how media technologies were considered to be disposable because they freed up human cognition, allowing for information to be “dynamic, stored, and in motion for instant recall.” Moving image formats cannot be owned in the same way as art (which is why it’s weird for me to think of VanDerBeek’s fax work in a gallery since it remains an artifact of a prior impulse and process).

In general, VanDerBeek’s argument for art to embrace disposability advocated for the rejection of the permanent art object in order to bring the processes of art and life closer together. For Levine, disposability allowed art to become something one does; it lets you “see as you move and [let] you move as you see.” Through film, television, and computational technologies, VanDerBeek similarly argued that the visual sensorium could more accurately approach the speed of life, where “all things move and are changing.” One matter of distinction between the two was that VanDerBeek condensed his concerns around new applications for moving-image formats; for Levine, this was only one aspect of the “beautiful disposable world.” However, both sought to loosen art from conditions of permanence and contemplation through the introduction of disposable techniques. What I didn’t write about, but should have, was how spirituality and Buddhism influences the focus on impermanence in both of their work.

<>Thanks for putting up with my typos and quickly typed essays <>